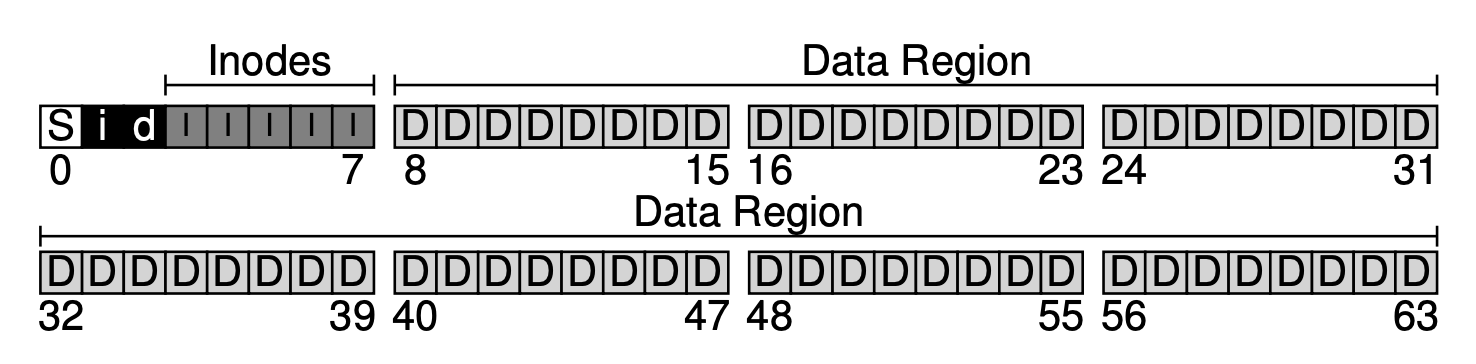

Overall Organization Of Data In Disks

Assuming we have a 256KB disk.

- Disk Blocks: The basic units of storage on the disk, each 4 KB in size. The disk is divided into these blocks, numbered from 0 to N-1 (where N is the total number of blocks).

- Inode Bitmap (i): Block 1; a bitmap tracking which inodes are free (0) or in-use (1).

- Data Bitmap (d): Block 2; a bitmap tracking which data blocks are free (0) or allocated (1).

- Inode Table (I): Blocks 3-7; an array of inodes, where each inode (256 bytes) holds metadata about a file, like size, permissions, and pointers to data blocks. 5 blocks of 4KB will contain 80 256 byte inode strutures.

- Data Region (D): Blocks 8-63; the largest section, storing the actual contents of files and directories.

Inode

Every inode has a unique identifier called an inode number (or i-number). This number acts like a file’s address in the file system, allowing the operating system to quickly locate its inode. For example:

- In a system with 80 inodes, numbers might range from 0 to 79.

- Conventionally, the root directory is assigned inode number 2 (numbers 0 and 1 are often reserved or used for special purposes).

The inode number is the key to finding a file’s metadata on the disk, and it’s stored in directory entries alongside the file’s name.

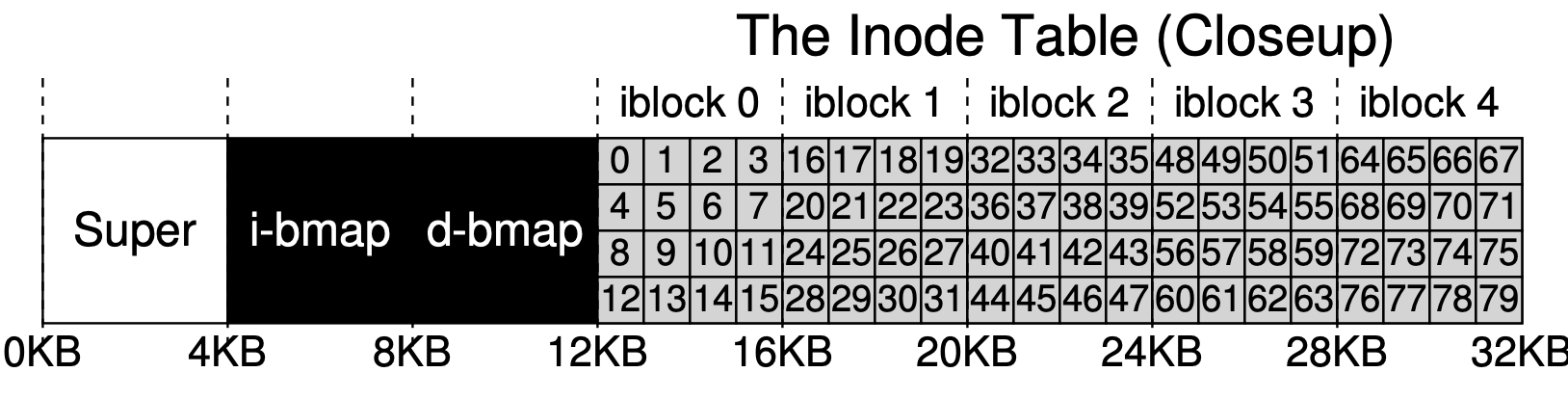

How Do We Jump to the Disk Block for a Specific Inode Number?

In a file system like vsfs, inodes are stored consecutively in an inode table, a reserved area of the disk (e.g., spanning blocks 3 to 7). Each inode has a fixed size—let’s say 256 bytes—and the disk is divided into blocks (e.g., 4096 bytes each). To locate a specific inode given its i-number, we calculate its exact position on the disk. Here’s how:

- Identify the Inode Table’s Starting Block:

- Suppose the inode table starts at block 3.

- Calculate the Block Containing the Inode:

- Formula: block =

(i-number * inode_size) / block_size + start_block - Example: For inode 10, inode_size = 256 bytes, block_size = 4096 bytes,

start_block = 3

(10 * 256) / 4096 = 2560 / 4096 = 0.625 → integer part is 0.block = 0 + 3 = 3.So, inode 10 is in block 3.

- Formula: block =

- Calculate the Offset Within the Block:

- Formula: offset =

(i-number * inode_size) % block_size - Example:

(10 * 256) % 4096 = 2560 % 4096 = 2560 bytes. - Inode 10 starts 2560 bytes into block 3.

- Formula: offset =

- Result:

- The operating system reads block 3 from the disk and jumps to offset 2560 bytes to access inode 10’s metadata.

This process allows the file system to efficiently retrieve an inode’s information and, from there, its data blocks. Since multiple processes may have file descriptors for the same file opened with their own data of offset to read from, multiple processes will be accessing the same inode structure to read about file and modify its data (Here inodes data would mean modifying things like last accessed time or adding another entry for list of data blocks etc), So i-node needs some sort of concurrency control in place. (More on this)

How does inode know the data it owns

An inode is a data structure in a file system that stores information about a file, including where its data is located on the disk. Instead of holding the file’s data itself, the inode contains pointers that reference the disk blocks where the data is stored.

- Disk Blocks: These are fixed-size chunks of storage on the disk (e.g., 4 KB each) that hold the actual file content.

- Pointers: These are entries in the inode that specify the locations of these disk blocks.

The inode uses these pointers to keep track of all the blocks that make up a file, allowing the file system to retrieve the data when needed.

What Are Disk Addresses?

Disk addresses are the identifiers that tell the file system the exact physical locations of data blocks on the disk. Think of them as a map: each address corresponds to a specific block, such as block number 100, which might map to a particular sector and track on a hard drive.

- For example, if a file is 8 KB and the block size is 4 KB, the inode might have two pointers with disk addresses like “block 50” and “block 51,” pointing to the two blocks that hold the file’s data.

How Does an Inode Manage Disk Blocks?

The inode organizes its pointers in a way that can handle files of different sizes efficiently. It uses a combination of direct pointers and indirect pointers, forming a multi-level indexing structure.

1. Direct Pointers

- The inode starts with a set of direct pointers, which point straight to the disk addresses of data blocks.

- Example: If the block size is 4 KB and the inode has 12 direct pointers, it can directly address 12 × 4 KB = 48 KB of data.

2. Indirect Pointers (Multi-Level Indexing)

For files too big for direct pointers alone, the inode uses indirect pointers, which point to special blocks that themselves contain more pointers. This creates a hierarchical, or multi-level, structure.

Single Indirect Pointer

This pointer points to a block (called an indirect block) that contains a list of disk addresses to data blocks.

Example: If a block is 4 KB and each pointer is 4 bytes, the indirect block can hold 4 KB / 4 bytes = 1024 pointers. That’s 1024 × 4 KB = 4 MB of additional data.

Total with Direct: With 12 direct pointers and 1 single indirect pointer, the file can reach (12 + 1024) × 4 KB = 4,096 KB (about 4 MB).

Double Indirect Pointer

This pointer points to a block that contains pointers to other single indirect blocks, each of which points to data blocks.

Example: The double indirect block might hold 1024 pointers to single indirect blocks. Each of those holds 1024 pointers to data blocks, so that’s 1024 × 1024 = 1,048,576 data blocks, or about 4 GB with 4 KB blocks.

Total with Direct and Single: (12 + 1024 + 1,048,576) × 4 KB ≈ 4 GB.

This structure acts like an imbalanced tree: small files use only direct pointers, while larger files use additional levels of indirection as needed.

Why Use Multi-Level Indexing?

The multi-level indexing structure is designed to balance efficiency and scalability:

- Small Files: Most files are small, so direct pointers handle them quickly without extra overhead.

- Large Files: Indirect pointers allow the inode to scale up to support massive files by adding more layers of pointers.

How It Works in Practice

When the file system needs to find a specific block in a file:

- It checks the inode’s direct pointers first.

- If the block number is beyond the direct pointers’ range, it follows the single indirect pointer to the indirect block and looks up the address there.

- For even larger block numbers, it traverses the double indirect or triple indirect pointers, following the hierarchy until it finds the right disk address.

This process ensures the file system can efficiently locate any block, no matter how big the file is.

References

- https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/file-implementation.pdf

- https://grok.com/chat/d429de0e-556f-426c-84bd-21ff1b0c4002 (Contains reference to actual inode structure implementation along with locks it uses on Linux)

- https://grok.com/chat/c86e3040-2f86-4aa9-a317-1c0a464564a3?referrer=website